Senior Distance Running Essentials Series

Chapter 9: Strength Training

Welcome back to Senior Distance Running Essentials. We now begin Part 2, which as a group is entitled Effective Training, Recovery, and Rehab for Seniors. These six chapters will draw from what we have covered in the first eight. I suggest reading those if you have not already done so.

We start with two chapters on strength training, then have two on training and racing strategies, and one each on recovery and injury rehab,

Strength Training is Crucial!

The importance of strength training cannot be overemphasized. Not only for our running but also for activities of daily living, or ADLs.

The objectives of a strength training program are both building and maintaining muscle strength and definition.. Strength training is essentially any form of resistance work and can be accomplished using various types of equipment — free weights, machines, straps and cables, and bands — as well as our own bodyweight. Sadly, strength training is often the last thing incorporated into a senior runner’s training program. The two main reasons seem to be a perceived lack of time and less than a full understanding of its importance.

Competing time demands

We all have many things to do revolving around work, family, community involvement, and time for other hobbies we are passionate about. Also critical is allowing for adequate rest sleep. However, many have found ways to carve out 45 minutes to an hour three or four times a week for strength training. Too much you might say? I hope by the end of this chapter, you are more aware of why this is a great investment of time as a means of warding off injury and maintaining lean muscle mass in all parts of our body as we age.

Muscle loss with age

As discussed in Chapter 4, we tend to lose muscle with age even if we stay physically active. Most of the research on muscle loss has been done with non-athletes, which may seem surprising except that most of the funding from NIH and other such sources is concerned with chronic conditions found in the general populace. In this so-called “normal” population, muscle mass typically peaks in the early 20s. Even with some level of physical activity, studies have shown men, on average, lose about 10% of their muscle by age 50, with the rate of loss accelerating thereafter. Loss in women tends to lag a bit behind men. By age 90, most people have about 50% of their peak muscle mass left.

Nirvana wrote a song “Half The Man I Used To Be.” I don’t think they were referring to muscle loss, but it certainly could apply!

Components of muscle loss

A decline in muscle mass is a result of both decreased muscle fiber size and number of fibers. Size reduction disproportionally impacts the muscles that provide peak power, such as sprinting or lifting heavy loads. We know these as fast-twitch fibers. However, fibers of all stripes decline in number.

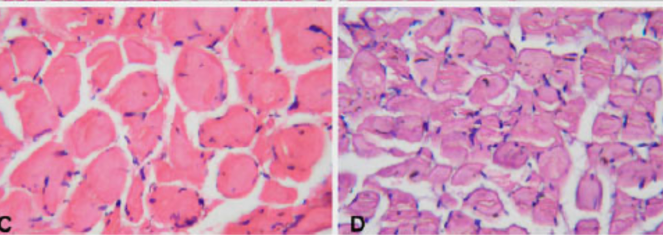

Here’s a slide from a study by Raesa Mohammed and others comparing muscle fibers from the triceps of two men: one age 35 on the left and another age 71 on the right presumably with similar levels of activity. The size difference is obvious and the total cross-sectional area, a measure of muscle density, of the older subject in this study was 30% less than the younger one.

Use-it-or-lose-it?

What does this tell us? First, maybe something of a use-it-or-lose-it syndrome is involved. We might think this “typical” 71-year-old was increasingly less active than the 35-year-old, though the research was designed to avoid that difference. Second, and this is of greater concern, various studies indicate there is a natural change with age in muscle quality and mass. In the next episode we will go into the gym to demonstrate exercises that offer ways to offset this natural loss. But just as our skin loses elasticity and radiance with age, muscle tissues also undergo changes.

What tp do?

So, the focus here will be on what we can do to attenuate the effects of aging on muscle. The benefits of doing strength training for the senior runner are many. Here are several listed in The Masters Athlete:

- Preserve Fast-Twitch Fiber. Targeted strength work can maintain more of the fast-twitch fibers, which will help preserve running speed.

- Retain muscle mass and oxygen uptake. Maintaining total muscle mass helps retain oxygen uptake capacity, which is essential in endurance running.

- Strengthen joints. Connective tissue surrounding joints is strengthened. This includes ligaments, tendons, and cartilage. And as we previously noted, failed joints are a primary reason for seniors dropping out of the sport.

- Bone density. This is maintained and even increased with strength training, perhaps avoiding stress fractures that tend to be more prevalent in runners as we age.

- Retain and improve muscle tone and posture. Aside from these physical benefits, retaining muscle tone and posture leads to improved self-confidence and function, not only in sport but in everything we do.

Strength defined

Let’s look at a couple of key definitions. First, strength is often defined as absolute — the maximum weight that can be lifted one time, or relative — the maximum amount that can be lifted once compared to one’s body weight. Even if I was a strongman — which I’m not! — I’d have little chance at 126 pounds of outlifting a healthy 200-pound man.

Strength endurance

Second, and very important to us, is strength endurance. When we run, we lift our bodies with each step. Assuming we are trained, that lift is a relatively small percentage of maximal effort. To run a 7:00 minute pace for a mile takes around 1,200 steps. To run a 10K, then, takes about 7,500 steps. So, we’re lifting that sub-maximal weight many times during a race. Our ability to do this, with good form of course!, is an example of strength endurance.

Power

Another measure of strength is power. It has to do with the speed with which we apply force.

This is an application of Newton’s Law of Acceleration. In sprinting, we push with full force until hitting peak speed. If we’re smart, we don’t build up to peak speed at the start of a long race! But during a race we may encounter a steep hill or decide to put on a surge mid-race or when nearing the finish. We’ll need some power to do that.

“Making an honest effort”

Thus, strength endurance and power will at times function on a continuum. At different points in a race, one may dominate. Also, we know what it’s like to feel an increasing level of discomfort in the later stages of a race in spite of running a steady pace. We might describe this as “making an honest effort” as we literally hold our feet to the fire. Having developed some power in our strength training will help us navigate this stage of a race.

Strength training variables

As we demonstrate various exercises in the gym in the next episode, I will explain the purpose of each along with a range of repetitions and sets you might choose to incorporate. Suffice it to say, there are many variables involved in a strength training program and it’s best to work with a strength and conditioning professional to determine what is right for you based on your training objectives.

Is upper body strength important?

As runners, we rely largely on our lower extremity. Why, then, would we be interested in building or maintaining upper body muscle and strength? The answer is pretty simple – we do more than run! I want to have arms strong enough to lift a kayak up onto the car roof rack. And there are plenty of seniors with slouched posture to remind us of the importance of upper back strength and flexibility. One accomplished senior runner noted in a focus group for this series that she finds her arm strength takes some of stress off her legs. So, it’s worth looking to incorporate a full range of strength exercises.

There are two key concepts to consider with strength training: progressive overload and specificity.

Progressive overload means adding more of some aspect of weight training incrementally, leading to adaptation, discussed below. The primary variables subject to progressive overload are:

- Maximum amount of weight lifted

- Number of repetitions of an exercise

- Number of sets

- Amount of rest between sets

- Frequency: # of training sessions per week

We have to be selective in which of these variables we increase, and by how much. There is no simple formula. Work with a strength professional you trust and help him or her understand your goals and objectives. In fact, strength training is an area where having clear goals really helps direct your efforts in a safe and effective way.

Specificity means doing exercises that that simulate the demands placed on muscles by running. This is why mufti-joint exercises, such as squats and leg presses, are good to include.

Safety first!

Safety is a crucial part of strength training. If we try to bench press 125 pounds just to prove we can do it, when we are really only conditioned to lift 95, we could injure ourselves or find the bar crushing our chest, with us calling out for help! Thus, having realistic expectations is important. For some exercises, working in pairs is a good idea. In all cases, correct form is critical in maximizing both the effectiveness and safety oof a strength training program.

Applying the concept of progressive overload and the five variables listed above, a key requirement is that we are taxing our muscles. This means we are lifting close to exhaustion whatever the number of reps. We have all seen older people in the gym lifting light weights, either on machines or free weights, maybe doing 10 reps without much effort. They could do 20 or more reps but stop at 10. I’d call this weight moving — not lifting. They are not doing themselves any favors. If we are not stressing our body, it will decline. This is a firm law of exercise physiology. The goal, then, is to incrementally stress our bodies and give them time to adapt.

When running for long periods of time, we’re calling on the quads to flex our hips and extend the legs, our calves to provide lift to enable float, and our hamstrings and glutes to repeatedly finish the gait cycle. No time off! Strength training of these muscles needs to involve some amount of over-loading to build that resilience.

The number of reps and sets naturally depends on the amount of weight. Endurance athletes often aim for 10 to 20 reps and do two or three sets. Again, it is important to approach exhaustion at the end of each set. More rest will allow for more reps, but an endurance runner may find it better to pull back on the weight in favor of shorter rest. These variables are not set in stone. They can (and should!) be varied week to week and month to month.

Frequency

Endurance runners are continually faced with a decision of how often to strength train. This depends on the purpose and intensity of the workout. I generally do some level of strength training along with stretching and foam rolling six days a week. But only on two or at the most three of those days do I lift to exhaustion. This is an important difference we will explore further in the next chapter in the gym.

Adaptation

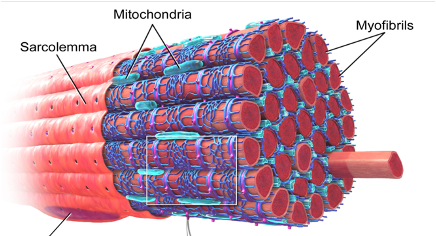

The principle of adaptation is critical to strength training, running hills or intervals, as well as many things in our lives. For example, when we first saw a multiplication table, it probably took a while to mentally grasp the patterns and relationships. But the neurons in our brain made new connections and once that happened, we could move on to more complicated mathematical constructs. The same is true with physical growth. Muscle cells grow by adding fibers, called myofibrils, within the cell.

Weight training and maximal run training do not grow new cells – they expand the ones that are there. Hitting our limits in the short-run destroys some of these myofibrils, which then must be removed and replaced. When this is done progressively, the volume of replaced myofibrils is increased. It doesn’t happen overnight – but it does happen. After a hard weight session, or a long run or race, we can be sore for several days as this process plays out.

Specificity

Specificity is the second fundamental principle of strength training. It’s important for our weight training to reflect the needs of our sport. A strength program should target those muscles employed in the running gait along the full range of motion. We want to be sure to mimic the movement patterns and loads around our hip, knee, and ankle joints. That’s how we run; so, that’s how we should strength train.

We already employ specificity by training at distances longer than our target races. By doing that we are not only conditioning our running muscles but also developing neural connections and enhancing our ability to transform glycogen and distribute glucose to the muscles. So, we can apply this principle to our strength training as well. Bottom line, both intense running and strength training are shoring up our capacity to run faster for longer distances.

Invisible gains

Assuming our objective is strength endurance, much of the gain from targeted strength work is invisible. Yes, it should result in improved definition and tone in our legs, shoulders and arms. We might even gain a couple pounds by adding lean muscle. But in the gym we could find ourselves working out side-by-side with folks bulking up – going for visible gains by lifting heavy weights for a limited number of reps. We are likely to be performing multi-joint exercises with lighter loads for a higher number of reps. As we have considered, this can still involve maximal effort, but rather than maxing out on the fourth or fifth rep, the endurance runner might near exhaustion on the 15th or even the 20th rep.

This is not to suggest bulking up is bad. Most endurance runners could stand adding a bit more muscle, though maybe not to the extent pictured here. Muscular guys or women running fast times in distance races are an anomaly. As with all things, we make choices that direct our actions. So, it may be good to ask yourself if you’re OK with the invisible gains.

It takes time!

Even if you lift heavier weights, it takes time to see visible results. You should notice within the first week the ability to lift more weight. But it may take five or six weeks before you see increased definition. What is happening is new neural connections are being made early in a strength training program. This results in more muscle fibers being recruited. Thus, even without increased muscle size, you can lift more.

Technique

Proper technique is critical in lifting. Not only in the form used but also in the speed of movement. Afterall, we are training the muscles to propel us at a good clip! If all our strength training is done in a slow and steady manner it will not prepare us for running fast. Good technique also supports the concept of safety first.

Where to strength train

Belonging to a gym makes sense for a variety of reasons, including having access to a pool for water running along with StairMasters or ellipticals for cross training and treadmills on cold, slippery days. Also, a good gym will have a variety of well-maintained machines, free-weights, and benches along with strength-training aids such as straps, stability balls, and BOSUs (BOSU is an acronym for BOth-Sides-Up).

People have varying reasons for being in the gym but it’s generally a supportive environment with trainers on site and others who might provide encouragement just by their presence.

I’ll close by emphasizing the importance of some maximal strength-training work. We know this approach from doing track intervals. We push it towards the max and after recovery we get to a new or returning level of speed. The same principle applies to strength training. Some of the work needs to be maximal to have the desired results. The practical side of this is when we are called to lift something heavy in our daily lives we have already done this in the gym. And the chances for straining something are greatly reduced.

We’ll be in the gym for the next chapter. And I’ll refer to much of what we’ve considered here.

We will also demonstrate some exercises that can be done at home.

Meanwhile, stay strong and regularly head to the gym!