Senior Distance Running Essentials Series

Chapter 13: Recovery (May 2024)

This 13th chapter of Senior Distance Running Essentials focuses on recovery while the next, and last content chapter, looks at rehab. Adequate recovery is critical in avoiding rehab! That is why this topic is arguably one of the most important in the series. If we follow a great training plan, eat well, and strength train but do not allow for adequate recovery, it may all be for naught and lead us toward rehab.

This is a good place to insert some words of wisdom from Peter Reaburn, who we’ve referred to throughout this series and author of The Masters Athlete. Peter’s mantra is: “Train Hard + Recover Harder = Better Performance.” He emphasizes that recovery is one of the most important training principles for athletes of all ages, but even more so with masters runners, for reasons we’ll discuss in a moment.

Reaburn concludes his chapter on this topic, suggesting that learning effective recovery strategies enables an athlete to:

- Monitor our response to training so we can cope with training stresses,

- Reduce injuries, illness, and burnout,

- Acquire effective life skills that go well beyond sport.

With so much to gain and so little to lose, I hope you agree this is an important topic. Let’s dig in!

Staying in the game!

Perhaps the key goal for us senior runners is still being out there while many of our peers are on the sideline. Recovery prepares us for the next hard workout or race. Dealing with niggling injuries is no fun and it weighs on us both physically and emotionally. For an endurance runner, there is nothing quite like lining up at the start, feeling well-trained, and hearing the gun or horn go off. It’s a happening, and we are part of it, whatever our pace or place. Just as important is being able to get up early and be out running as the sun rises. Or meeting fellow runners in the afternoon for a track workout.

Why, then, do seniors skimp on recovery after an event or hard workout? Here are a few reasons I’ve drawn from The Masters Athlete:

- We underestimate the value of recovery, either because we have not paid attention to the science, which is conclusive, or we somehow feel we are exempt from the effects of hard efforts and expect things to work themselves out in a day or two.

- Others’ expectations. We have workouts planned with others, and don’t want to be seen as a “laggard.” This can evolve from group think, where we assume what others are thinking. Why not speak up: “Hey, we ran a hard race on Sunday, let’s go easy today.” If they still want to go hard, there will be other group workouts.

- Only the strong thrive syndrome. We’re pretty sure working hard will give us better results. We don’t want to waste a workout, and

- Our workout time may be tight. If we only have time for four or five runs a week, we are going to make the best use of those sessions.

These four reasons illustrate that training hard may not be training smart.

So, what is the science telling us about why seniors incur more damage from intense efforts than younger runners, thus underscoring the importance of recovery? Here are some reasons, also cited in The Masters Athlete:

- Decreased muscle size and strength. As we have examined, in spite of doing strength training, we have a tendency to lose muscle size and strength with age – what is there must work harder and is thus subject to more damage.

- We also tend to be less flexible and pliable. This leads to decreased range of motion around our joints. We hit resistance to motion earlier in our gait, leading to more tissue damage.

- Decreased inflammatory response. When we looked at the immune system, we noted our inflammatory response begins the repair mechanisms. Yet with age that response takes longer. Thus, full recovery takes longer as well.

- Our senior bodies show a decreased rate of protein synthesis, which in turn slows the rebuild of damaged muscle.

So, we seniors have some constraints to consider when looking at recovery. A key takeaway is time is on our side. Meaning, if we allow enough time, and follow the principles we’ll discuss next, we can and should be able to recover well and not set ourselves up for injury.

Recovery Principles for Seniors

OK. Let’s look at some recovery principles. These have been developed over a number of years and apply to athletes of all ages. However, for the reasons we’ve just noted, the duration of recovery for seniors is often longer.

Principle #1: Harder means longer recovery

- Recovery duration is longer for harder efforts. Racing a 5K has a different impact than a half marathon or marathon, especially if we truly race those longer distances. Also, some races and training runs have endless hills while others are pancake flat.

Principle #2: Start pronto!

- Recovery is most effective if started immediately. This includes an immediate cool-down followed by hydration and nutrition, and ultimately rest. In younger years, we might have tacked on a 10-mile run after a hard 10K race to get in our 20 miler. Not a good idea for seniors.

Principle #3: Running is just part of our lives

- Life would actually be pretty dull if running was all we did. If our lives are balanced, we’ve got a lot of other things going on. In total, this adds up to increased stress aside from running, which is likely to impact our recovery.

Principle #4: Individual differences

- And of course, we truly are experiments of one! Two people running a hard workout may find one feeling sore or exhausted while the other is feeling energized and ready for more activity. And that may vary between those two people from day to day.

Not surprising, this area has drawn attention in the research world. Dr. Michael Kellman has written a book on this topic entitled Enhancing Recovery: Preventing Underperformance in Athletes that may be of interest to you. Kellman prioritizes recovery strategies under the headings of nutrition and hydration, sleep and rest, relaxation, and stretching/cooling down. The point here is that there is no simple formula to follow. Yet, you are not on your own with this. There are resources to help guide you. But ultimately you must experiment to find out what works best for you.

Adaptation & Recovery

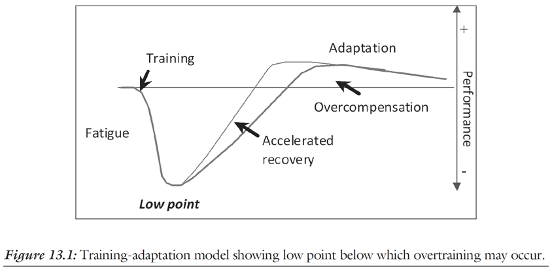

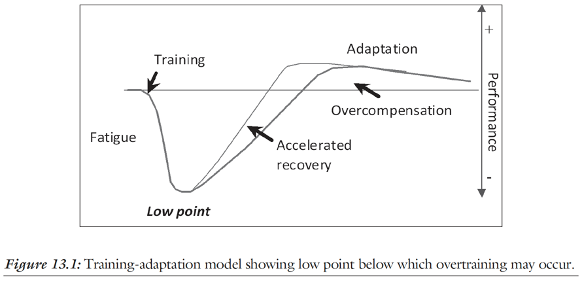

I suppose we could consider adaptation a 5th principle. The below table created by Dr. Aaron Coutts shows how performance is negatively affected by fatigue and then rebounds, or adapts, to a point where the athlete sees net gains. If we do this right and give our bodies enough time to recover, we emerge as strong orstronger.

This is a result of what is called overcompensation. The chart shows adaptation happens more quickly if fatigued systems are restored quickly. As noted, we seniors respond slower than younger athletes, so we need to be doubly careful to allow enough time to pass for adaptation to happen.

Improve or maintain performance?

Now let’s consider possible differences between a younger athlete looking to improve performance and a senior runner looking to maintain or minimize loss in their level of performance. The principles are the same, but instead of aiming for overcompensation, the focus might be on getting back to where we started after a hard race or workout. This is tricky. At what point do we stop trying to improve? Is this not part of what makes being a senior runner rather fascinating business?!!

Applying periodization

This takes us back to what we looked at in the prior chapter about periodization, which is essentially a planned, voluntary reduction in training, in contrast to injury when the choice is made for us. Within the course of a year, a 70-year-old might back off in the intensity of his or her training, resulting in slower race times, with the intent of later in the year ramping back up and returning to, or largely returning to, prior performance. We might get antsy about pulling back – invoking the use-it-or-lose-it precept. Yes, we are aging, and yes, substantial time off from exerted effort will work against us. But our bodies follow a rest-recovery cycle at any age. We can trust that. Ultimately, it’s our job to pay attention to how our body feels and respect that.

Recovery Strategies

So, let’s draw from what we have covered to look at some specific recovery strategies.

#1. Cool-down

We looked at cooling down as a training strategy in the last chapter. Here we look at cooling down as the beginning of the healing process. We considered how the cool-down typically includes jogging, walking, some light stretching and should be easy, not an add-on to a race or intense effort!

#2. Stretching and rolling

After the jog, it’s good to do some static stretching to help elongate fibers that may have shortened during the race or workout. These are longer stretches, maybe 15 to 20-seconds.

Do not hurry. Select a few stretches that get at all the stressed muscles. Relax into the stretch. In particular, make sure to target the calf muscles, hamstrings, and quads. Preceding and/or following this, a few minutes with the foam roller helps stretch surface muscles.

#3. Hydration and fueling

As we discussed in the episode on nutrition, fueling and hydration practices are critical both to performance and recovery. These needs will differ if we’ve hydrated and taken nutrition during our run or race. For shorter distances, no need to go crazy with either of these things. Under normal conditions and shorter race distances, we have plenty of water and energy in our bodies to get to the finish. Especially if we’ve done pre-race nutrition and hydration.

#4. Sleep

More and more is being learned about the importance of sleep. The science is telling us that society’s penchant to habitually under sleep is working against us, negatively affecting our overall health as well as athletic performance. During sleep, our body produces cytokines, a hormone that supports the immune system. The latest evidence emphasizes the quality of sleep is as important as the quantity. The National Institute on Aging suggests that while seniors do not necessarily need more hours of restful sleep, often our sleep is disrupted by waking up more and having trouble going back to sleep. Thus, to get eight hours of quality restful sleep might involve being in bed longer.

In an article from the Sleep Foundation, Fry and Rehman suggest those who engage in “moderate” levels of exercise need less sleep than “elite” performers. However, in the general population the bar for exercise measurement is pretty low, and while we may not consider ourselves “elite,” most serious senior runners are putting in hard workouts, suggesting a need for an increased amount of sleep. This comes back to our own perception — meaning, do we wake up feeling rested?

# 5 Non-running exercise

We looked at Deep-Water Running (DWR) in chapter 12 as a training strategy – a way to add aerobic activity on non-running days. But it is also valuable in recovery after an intense effort. Water running allows for a full range of motion and has a rather unique way of mimicking our running gait while flushing blood through injured tissues. It is also an activity that is hard to overdo since there is no pounding on the joints. Of course, you would want to avoid performing intervals in the water when using it as a recovery activity! Other REQs, such as StairMaster, cycling, and swimming can aid in recovery, as long as these are not done at an intense level.

#6. Other modalities

There are many proponents of hydrotherapies as a recovery strategy. Hydro, of course means water. I have not tried alternating hot/cold showering or submersion methods, but the evidence is pretty strong this helps in recovering from hard efforts. I have sat in the hot tub and placed my leg against the jet stream and this seems to help loosen things up. Having access to a hot tub is problematic though. Many gyms have saunas but fewer have hot tubs, as they are harder to maintain.

Massage is great! Though from a practical standpoint, it’s rarely an option right after a hard workout. Scheduling an appointment might not synch with a race or our training. Self-massage can provide some of the benefits a therapist can offer. Foam rolling, The Stick, and other such implements can help too. However, we can make things worse by going at it too hard right after a race or hard workout.

Properly done, yoga is a go-to recovery option for many runners. Find a yoga teacher who regularly runs, and ideally races, so they know your mindset and priorities. Some practitioners make yoga their primary form of physical activity. Most runners are looking for a complementary activity that supports and not displaces their running.

Overtraining vs. Highly Trained

Before we leave recovery, let’s consider something to watch out for — Overtraining. We probably have had plenty of experience feeling when things are “coming on.” There is a fine line between being highly trained and overtrained.

Being overtrained means we’re on the brink of injury. So, recognizing the signs are important. Here are a few noted in The Masters Athlete:

- Constantly Tired. We’re flat-out tired much of the time, feeling physically drained, maybe nodding off at work or in the evening before bedtime.

- Low-grade illness. We have a constant sore throat or sniffles.

- Grumpy! We’re unusually grumpy and quick to either express or feel anger. OK, we all have our moments, but it’s a consistent pattern that raises concern.

- Unenthusiastic. Our eagerness for getting out to run wanes and when we finally make it out, we’re slogging throughout the run.

Let’s revisit Aaron Coutts’ graph modeling training adaptation. Note the low point. This is where an athlete is most susceptible to overtraining. And this is where the signs we just looked at can be most helpful. We need to give our bodies enough time to recover and move back at least to the initial training level before pouring it on in our training.

If you find yourself on the brink of overtraining, immediately cut back on your running volume and intensity. Probably good not to run the race you had planned on during the upcoming weekend. There are plenty of races down the road!

In this chapter, we have looked at some theory, some practical applications of this theory, and a few specific strategies you might wish to include in your training. This may be a good time to reflect on what you have been doing, what has worked well, and what has not. The goal is to be able to run well into our senior years and that will likely result in making some changes to the way we have trained. Doing this should provide renewed optimism about being able to manage the aging process, at least as it relates to our running.

Prehab

As was suggested, there is a thin line between being well-trained and overtrained. Much of what we have looked at in this chapter and those on strength training and other training and racing strategies might be considered Prehab, a popular term used to describe proactive actions to avoid injury. Prehab literally means “to stay ahead of rehab.” I hope this series will help you do that!

The next and last content chapter will be on rehab, something we obviously look to avoid, or at least minimize. I hope you return for that.