Senior Distance Running Essentials Series

Chapter 14: Rehab (May 2024 Update)

This is the last content chapter of the Senior Distance Running Essentials series, which is presented on TheSeniorRunner.com website. Eventually I hope to add audio or video interviews with experts, drawing from what we have covered.

As noted throughout, a big challenge has been to decide how much to go into depth on each topic. The series is admittedly a brief overview of the various aspects of senior running. Ideally, SDRE has served to increase your awareness of the ranger of issues we face as senior runners. Please subscribe so you can be alerted when new blog posts or other content is added.

This last topic is rehab. We do our best to avoid rehab but as we know all too well, injury is part of our sport, with over 50% of runners experiencing some kind of downtime during the course of a year. Repeated cycles of injury impact our enjoyment of the sport. Regular visits to our physical therapist are not how we wish to spend our time and money.

Why Am I Running?

A key objective for creating this series is to help other senior runners avoid both the niggling and serious injuries that put that ominous question before us: Why Am I Running? Is it really worth it?! Presumably we have answered “yes” to that question and are sticking with it.

So, for whatever reason, we find ourselves rehabbing something. Rehab can be used as a verb or noun. It’s short, of course, for rehabilitation, which relates to all types of human activities and conditions. In running, and really all sports, the intention is to return to sport.

Rehab vs. training

Rehab is not training, per se, though it uses some of the same processes of repair and re-building of tissues. When rehab finds us, it requires immediate adjustments. Most runners of all ages set their race schedule months in advance, often due to either our favorite events or regional race series where we look to duke it out with our long-time competition. This planning may be more targeted for senior runners as we cannot (or should not!) be racing 30 or 40 times a year, as maybe we did in our 30s and 40s.

Thus, when rehab us upon us, we may experience the various stages of grief, starting with denial and ending in acceptance. This is to be expected! — We have worked really hard to stay in shape and be ready for action. And to not be in planned races or if there, not be at our best, is disappointing.

The first order of business is to figure out why we’re injured. It’s easy if we stepped off a curb wrong or got stuck in a pothole and twisted an ankle. Often, it’s more subtle and due to cumulative forces from too-much-too-fast, bad running form, muscle strength imbalances, or inflexible joints. Maybe all four! If we can discern the likely culprit or culprits, we have a starting point. It’s important to be honest here — something may have been coming on for days, weeks or even months and if we’re in the racing season we may have chosen to ignore it. Rehab from a chronic injury is often more involved than an acute injury. And even if we have recovered, if we don’t know why the injury happened, it’s hard to make changes in our training that give us the best chance of staying injury free.

Professional assessment vital

In spite of doing a lot of research on the Internet, it is often necessary to get an exercise professional to assess our injury. They have probably seen similar injuries in others and can help us sort through the options. MRIs can show various layers of tissue and that allow us and our providers to home in on the problem. Once we have a good sense of the source, then we need to honor and fully support the body’s three-phase response to injury:

The Healing Process: Inflammation /Proliferation/Remodeling

Healing starts with inflammation, a painful phase but needed to begin the repair process. While we may not like it, inflammation is our friend. We may try to mask it with ibuprofen but this can actually extend the process. Proliferation leads to the first growth of new cells, the rate of which varies significantly among tissues. Skin growth happens quickly; bone takes much longer. Remodeling puts the finishing touches on repair processes. For reasons we have looked at throughout the series, all three of these processes slow with aging. Thus, patience is needed! Letting things settle may take some time, maybe a lot of time depending on the injury. It is important to determine what types of activities can be done without aggravating the injured tissues. Nevertheless, it is vital to stay active!

Mimic running

You may need to push the envelope to find exercises that mimic running. Maybe this starts with walking, and then moves on to water running, elliptical, or StairMaster. This is best done with professional help and will likely involve some trial and error, with progress happening on a continuum. Once tissues have responded sufficiently, light jogging, perhaps interspersed with walking, will help maintain running endurance. Then gradually, and your body will inform you on this, increase running activity.

Ramp up distance, then speed

Generally, it’s prescribed to first increase distance, maybe getting up to five or six miles, before significantly stepping up the pace. Speed puts more stress on our tissues. It may be many months before you can approximate pre-injury pace. This is why it’s called rehab and not training!

Rehab is slower for seniors

We can no doubt remember a particular injury we had years ago and recall the approximate time it took to rehab. The crux there is “that was years ago.” While it depends on the specific injury, the evidence suggests it takes about twice as long for a 60-year old to rehab an injury than someone in their 30s. And if 60-year-olds are feeling sorry for themselves, someone 75-80 years old can expect rehab to take three times as long. That doesn’t seem fair, but it’s the way it is!

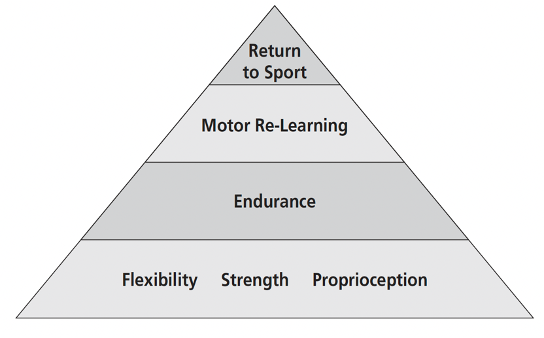

Here’s a diagram of the Pyramid of Recovery from The Masters Athlete.

This process will vary by individual and by type and extent of injury, but these general steps will need to be followed.

Base of the pyramid

At the bottom, we see regaining joint flexibility, strength of key muscles, and balance as primary steps. This does not happen overnight and it’s important with each step not to aggravate the various structures that are healing. If there is aggravation, we go backwards and restart the process.

Endurance

Gains back in both muscular and cardiovascular endurance begin with lower load efforts and then ramping up. We cannot expect to race at a pre-injury level on our first race back. or even in the first weeks, month, and depending on how long we’ve been out, maybe months back. It’s a process that is directly affected by how long we have been unable to function at a high level. Cardio endurance can often be largely maintained by extended water-running sessions, if the injury allows for that. Regaining full cardio and muscular endurance takes creativity, diligence, and patience.

Motor re-learning

We didn’t have the chops to run nearly all-out when we first started running. Even though we know the feeling of going up on our toes as we see the finish line, we can’t expect after significant time off that this just magically returns. We must increase the frequency, intensity, and duration progressively so that we are ready to move into the last level of the pyramid – full return to sport.

Return to Sport

This is likely to happen in stages. We may need to regain our speed with shorter races and then move up in distance. If racing longer, we will likely need to be willing to adjust expectations for a while, without letting ourselves off the hook. This can be a time when the competitive senior runner is feeling vulnerable and even a bit shy about showing up at races. In Elements of Effort, John Jerome describes his experience of “turning the screws” when hitting his upper limit in a race. Our memory of what that feels like and the experience of moving through it is something that may need to be relearned.

My own experience

Recently, I dealt with an injured proximal (upper) hamstring tendon. I’ve had my share of hamstring issues over the years, but at age 74, something was different. I had run with a nagging hamstring for six months, achieving sub-optimal results. It would get marginally better, than worse again. I finally got some help. An MRI showed a partial tear of the tendon, probably something that happened because I never let a strain fully heal. My doctor suggested a platelet-rich plasma (PRP) injection. Post-PRP, I was cleared to only walk and water-run for four weeks, followed by some very easy jogging interspersed with walking. Having no adverse reaction over several weeks, I was then cleared to incrementally build up. I entered my first race 14 weeks after the injection, understandably at a pace much slower than pre-injury. The build-up from there continued incrementally. In total, this rehab process took about ten months. A long time! But the alternative was a recurring hamstring injury. I now do regular hamstring-strengthening and stretching exercises in hopes of not seeing this injury recur.

Rehab is not fun

Sufficed it to say, we don’t seek out rehab. We run to run, not rehab. But this is where the golfing analogy of “playing the ball where it lies” might apply. Golfers don’t choose to be in the trees, sand trap, or deep rough, but they know where they want to go – to the flagstick and into the hole. We may want to run a strong 10K in three weeks but find ourselves in the rough. We need to get ourselves out of the rough and onto solid footing. Maybe that happens in three weeks or three months, or longer. We must be prepared to accept what our bodies will allow while being proactive in working our way back into form so we can show up ready.

Our last content chapter

This is the final (and shortest!) chapter of Senior Distance Running Essentials. If you have read the entire series, I hope you have found it useful. As I said in Chapter #1, it is intended to fill a niche, a comprehensive consideration of various aspects of senior distance running targeted towards the 150,000 of us still hitting the roads and trails.

I want to express my appreciation for fellow senior runners who have reviewed the materials and provided feedback. I would have missed much more without their help. These contributors are noted in Chapter 1 and on the SDRE home page.

As I have noted throughout, my reading of The Masters Athlete, written by Dr. Peter Reaburn in 2009 when he was the Exercise and Sport Science department head at Central Queensland University in Australia, has been an impetus for creating the SDRE series. This book is no longer available, but has served as an inspiration and source of much valuable information presented in this series.

Another steadfast supporter of this work has been Dr. Karen Westervelt, an associate professor in the College of Nursing and Health Sciences at University of Vermont. She encouraged my efforts when I returned to school as an older student with an interest to get “under the hood” and see how our running bodies work biomechanically and how aging affects that.

I hope to arrange for audio or video interviews with both Peter and Karen and include these on the website.

Thank you for sticking with it! My best wishes for good health and happy running!