Senior Distance Running Essentials

Chapter 11: Training and Racing Strategies, Part 1 (May 2024 Update)

What we’ve looked at in the prior chapters provides important background for what we will cover in the next two: Training and Racing Strategies for Senior Runners, Part 1 & 2. Let’s briefly recap the key points covered so far:

- We are all subject to aging processes at both the cellular and structural level. While this proceeds at different rates in different people (as we have noted, we are each experiments of one!) I hope you have accepted that aging is happening and we must allow for that in our training.

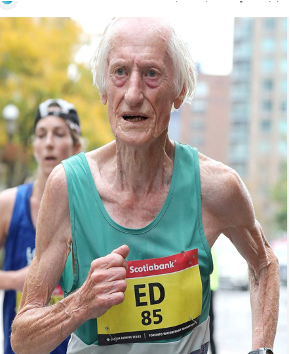

- Aging affects our running biomechanics. However, we have seen examples, such as Ed Whitlock, who into his 80s persisted to exhibit fine running form. We’ve considered how things line up in the kinetic chain, from our head to toes, to facilitate good running form and economy. We have considered how strength training and flexibility exercises support running biomechanics as we age.

- We have examined some hard truths about how the cardiovascular and respiratory systems change with age. The delivery of blood filled with nutrients and oxygen into the cells and then the extraction of carbon dioxide and wastes from them slows down. Maybe our rate of change is half that of sedentary people, but it is happening, nonetheless.

- We have also considered how aging changes basic nutritional and hydration needs. We simply do not absorb nutrients as efficiently in our 60s and 70s as in younger years. Changes in our body composition — in particular a greater % of fat vs. lean muscle and a reduced % of water content, suggest we need to give close attention to the quality of our diet and make sure we regularly hydrate.

- Changes in recovery time supersede approaches to training that may have worked well in younger years. While we have touched on this, chapter #13 will consider this in more depth.

- Finally, strength training is imperative for a senior runner. We addressed this in the last two chapters. Losing strength and muscle with age is the normal condition. We need to proactively offset that with a rigorous program of strength training!

In this episode we will look closely at three training strategies senior runners might consider incorporating:

1. Goal setting

2. Training logs

3. Age-grading tables.

Goal Setting

Setting goals is both an art and a science. Since goals must consider the context in which they are made, and since aging presents us with an increasing number of variables, it’s fair to suggest setting goals for the senior runner is both more difficult upfront and likely to require more frequent review than when we were younger.

Objective and subjective goals

Goals are often considered subjective or objective. For a competitive senior runner, meeting subjective goals, such as “Staying Healthy” or “Keep Running,” might be assumed. Thus, we can turn our attention to objectivegoals, which have a particular target, or object, in mind.

Objective goals can be further subdivided into process, performance, and outcome goals. We’re going to look at examples of each.

Goal setting screens

To have the best chance of effectively channeling our efforts, objective goals, whether they be process, performance, or outcome goals, should incorporate four elements, or screens:

- Realistic but moderately hard to achieve. Otherwise, why bother!

- Specific, leaving no doubt what we are seeking to achieve.

- Have both Short-Term and Long-Term components. Some goals may be split into weeks, months, or even years.

- Built-in Feedback Loops. Feedback has been shown to bolster motivation. This screen is supported by maintaining a training log, which is our next topic.

Let’s consider three possible process goals for a 65-year-old runner who wants to run and possibly race at least until age 80.

Process Goals

- Train six days a week, with at least one and ideally two of those days involving non-running aerobic activities, such as the elliptical, deep-water running, swimming, cycling, or StairMaster. This frequency allows for establishing and retaining a training rhythm.

- Unless injured, average 25 running miles per week, or 1,300 miles per year.

- Maintain a strength training program targeting all major muscle groups three times a week.

I suggest these three clearly meet the 2nd, 3rd, and 4th screens. Meeting the realistic screen depends on being free of injury. If injured, the running will need to morph into another aerobic activity.

Performance Goals

Let’s move on to two possible performance goals:

(1) Run 12 to 15 races from 5K to half marathon during the next 12 months;

(2) Attain at least a 75% age-grading in 10 or more races. (This could just as well be 65%, 70%, or 80% depending on the runner.)

These are related. While some races might serve as hard training runs, “just showing up” does not cut it for most senior runners who are putting in the work. Races give us on opportunity to test ourselves. Assuming a runner has previously performed near or at that level in AG%, I suggest these two goals meet all four screens. If road race times are not a priority for you, then choose something else that is measurable. For example, completing three triathlons or six trail races.

Outcome goals

Outcome goals are tricky. We have to be careful that meeting them is not largely contingent on what others do. Let’s consider a possible outcome goal:

“Finish in the top three for the year in one’s age class in the USATF-New England race series.”

What is within our control is having adequately trained and being able to race. And this goal might assume the runner has previously raced at that level. If this runner finished 10th place the prior year, this goal may not be realistic. What is out of our control is who shows up at the races or who ages-into the age class that year and may be up to five years younger. So, maybe this goal meets the screens, but it depends on some things outside of the athlete’s control.

Bottom line, goals are meant to be guides, not obsessive task masters taking on a life of their own. Periodic assessment is essential, with adjustments made as needed.

Training Logs

Now we’re going to talk about a tool I’ve use for many years: keeping a training log. This also helps us track goals.

I am sure the younger set might laugh at my hand-kept calendars and logs. Some now use Strava or other online tools. Maybe that works OK. Find what works for you!

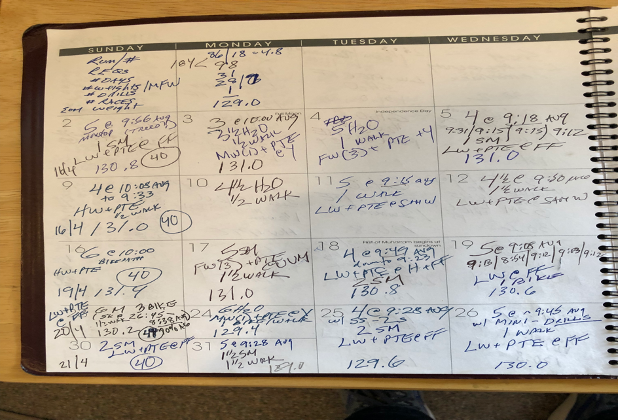

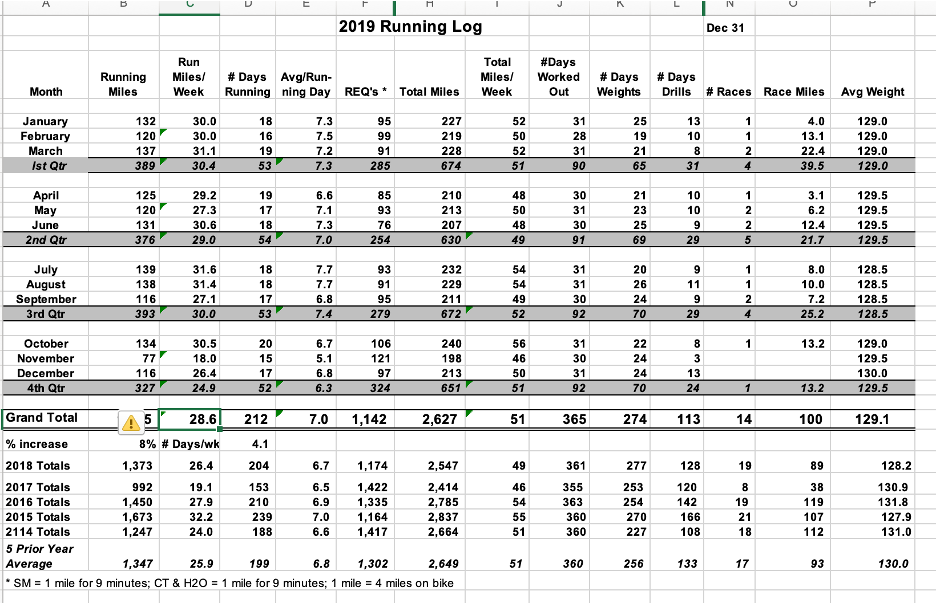

Here’s a page from a recent monthly log. There’s enough space in each day to log what I did, where I ran, how it felt, and the pace. At the end of the month, I total up what I did for each training element compared to goals I set at the beginning of the month for #miles/#days, total running equivalents, days of weight training, days of running drills, and end of month weight.

Here are five ways I use training logs, which I have kept for the past 30+ years:

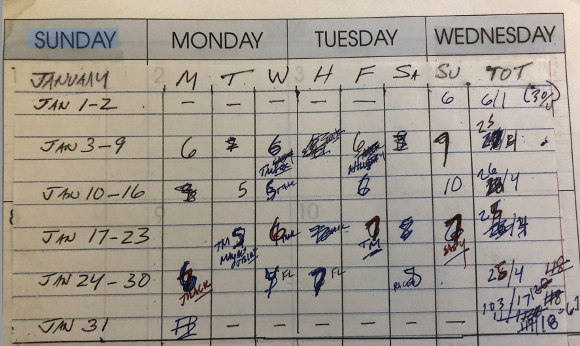

- Track and plan for training cycles. At the beginning of each month, I sketch out my training by week: which days, long runs, track workouts, as shown here.

This is essentially a combined macrocycle and microcycle approach, something we will discuss in the next episode on periodization. As the month unfolds, I update it. It gets pretty messy because I always end up changing it.

- Injury management & surveillance. The monthly log provides vital information. If I felt something tweak, it’s noted in the log — and I track that in subsequent days until it’s not an issue. If I’m having PT, I can look at this with my therapist and it helps guide treatment. The log tells me how long it took to recover from an injury. Entries from prior years may help inform a current injury plan.

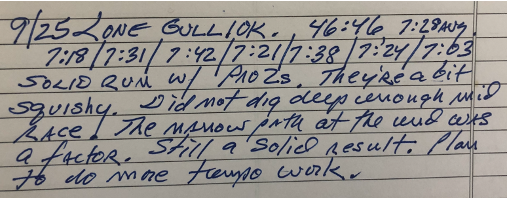

- Documents tapering for races and recovery. For example, in September 2022, I ran the Lone Gull 10K. The log showed my last long run was 10 days before the race and last track workout 7 days before, then easy for five days leading up to the race. The race went well! However, I noted that a long run one week after the 10K was tough, suggesting I still hadn’t fully recovered. Good to know!

- Commentary on how things are going/feeling at different times of the year or during a race. Above is an entry written after running that race. It shows mile splits and overall pace, how it felt, and brief takeaways. Below is summary by month for the entire year.

Note at the bottom I keep totals for the past 5 years. This helps me stay grounded. For example, I ran just 992 miles in 2017 due to injury. Thus, it would not have been wise to plan to run 1,500 miles (a 51% increase!) in 2018. As it was, I ran, 1,373 miles, a 36% increase – too much by most standards. But this is where running equivalents come in, which we’ll look at in the next chapter. In 2019, I ran 8% more miles than in 2018, a more sustainable increase.

This might seem like a lot of busywork and to be honest those I have coached have been less than enthusiastic about keeping such a detailed log. But it has worked for me for one basic reason:

It keeps me accountable!

The numbers don’t lie and the commentary helps me see beyond the numbers.

Find a log method that works for you, but I am quite sure over time (remember we are in this for the long-haul!) you will find this a useful and revealing exercise.

Age-Grading

I’ll admit when I was in my 40s and still running close to PR times, I sort of stuck my nose at age-grading. “Run the races and let the chips fall where they may!” But I’ve mellowed with age (not a bad thing!) and am now an advocate.

First, let’s look at what age-grading is. Age-grading tables were first issued in 1989 and then updated in 1994 by National Masters News in conjunction with the World Association of Veteran Athletes. They covered track and field events as well as road race distances. The tables were compiled from world-best times for each event for every age, calculating a percentage of a projected or actual time to this best-ever time. Meaning 100% would be equivalent to running the world record! The following categories were developed:

[90-100%: World class

80 to 89.9%: National class

70 to 79.9%: Regional class

60-69.9%: Local class]

Naturally, there is a significant difference between 80% and 85%. For example, a 70-year old male running a 42:04 10K would have an 85% AG%, whereas a 44:41 results in an 80% AG%. Pretty big difference!

How rare is an 80% age grading? At the 2022 New Bedford Half Marathon, which attracted nearly 2,000 runners including many of the top New England runners, only 11 women and 32 men achieved an age-grade % of 80% or better — about 2% of the field. We would expect this. How many national-class runners can we expect to show up, even at a regional championship race? An outlier are the USATF national masters championship races, which attract strong fields from around the country. For example, at the 2024 James Joyce Ramble 10K in Dedham, Massachusetts, 12 of the 285 finishers achieved 90%+ and another 99 at 80%+. Thus, 39% of the field was 80% or better. To boot, a total of 218 runners (76% of the field) exceeded 70% age grading. That is an outlier!

As noted, the tables are compiled for each age. So, a 71-year-old male would only need to run 45:09 to earn an 80 AG%, rather than the 44:41 needed when he was 70.

This method allows for comparison of runners of different ages. In fact, many races are now providing results in net time and age-grade percentage, often combining both men and women for age-grading results.

As world-best times for many road events have improved since 1994, the tables for long distance events were updated in 2004, 2010, 2015, and 2020. It’s likely this five-year cycle of updating will continue. Compiling this data has been a labor of love, mostly by volunteers through groupings representing the USATF Masters Long Distance Running (LDR) committee. These are considered world standards even though they’re issued by USA Track and Field. Here is the to the current 2020 MLDR tables: .

http://www.howardgrubb.co.uk/athletics/mldrroad20.html

So, how might we use age-grading tables in our training and racing?

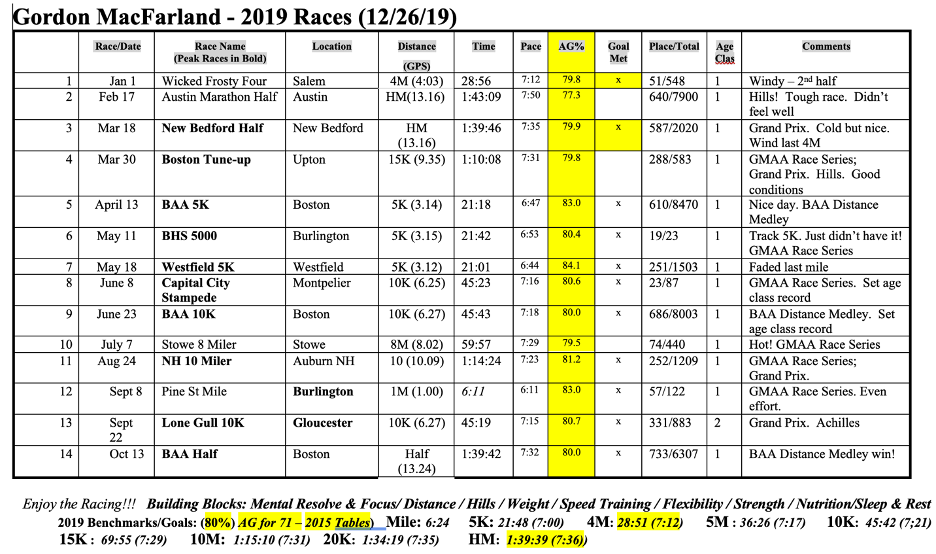

As an example, here is my racing summary when I was 71. Let’s look specifically at the AG% column, shaded in yellow. One of my performance goals for the year was to run at least an 80% AG% for each race. This goal seemed realistic as I have been able to achieve this % over the past number of years. It’s also under my control. Who shows up doesn’t change my %. Of the 14 races run, I met that goal 11 times, and considered it a successful year.

Please note at the bottom of this table the time and pace needed for 80%. And you might see in two cases I marked meeting the goal when it was slightly less than 80%. This was due to my practice of relying on my Garmin GPS watch for the pace and distance. All of these races were on certified courses, and you may not know there is a .1% fudge factor built into certification measurement. Thus, a runner is assured a certified 10K course is at least 6.207 mile. One reason, along with providing assurance as to distance, is if someone sets a national or world record, this buffer ensures any small error will be covered. In addition, certified courses are measured for the shortest possible distance. The certifier measures right up to the curb. It’s nearly impossible to run an entire course this way, especially if running in a pack. So, the Garmin tells me what I actually ran.

However you choose to compile your race results, age-grading provides a consistent way to measure your results. Yes, some courses run faster than others, and conditions some years are more favorable than others. Assuming similar conditions, age-grading offers a way to compare year-over-year how we perform at a particular race as we age.

Is age-grading hocus pocus and a way of deflecting the reality we are aging? As I said, I once held this view. No longer!

In the above race history record, please note the various metrics I tracked. Yours might be different. These are important ones for me. And the comments column, which might also be entitled “Excuses” provides some context about what happened that day. I have these race history pages going back to 1986 and usually once a year I look through them. I am amazed how many of those races I can still vividly recall! Running and racing is like that – it sticks with us!

So, in this chapter we have looked at three training and racing strategies you might consider. Goal setting has been demonstrated to help focus runners’ efforts of all ages. If you’ve already employed this approach, I encourage you to look at ways you might expand its use. As to training logs, my method is admittedly long hand. Maybe a streamlined approach will work for you as well as online options. And age-grading, now over 30 years old, is one way to compare our senior selves to other seniors and to our earlier selves.

Our next chapter will focus on periodization, which is a key strategy to avoid overtraining, running equivalents, maintaining our running gait, as well as warm-ups and cool-downs. These are important topics for runners of all ages but we’ll look at them through the lens of aging. I hope you check out that chapter.