Senior Distance Running Essentials Series

Chapter #2: Why We Run; Why We Stop (May 2024)

Welcome to the second chapter of Senior Distance Running Essentials.

This chapter asks two questions: Why we run? and Why we stop? Ask a runner what they enjoy about running and brace yourself for a detailed account of the reasons. If you’re at a race or a club dinner, the chatter is nonstop! As it should be – running means a lot to those of us who have endured over many years.

Why We Run!

A few years ago, I had dinner with Ed Whitlock, who we watched running in the first chapter, and Bill Dixon at the Stockade-athon in Schenectady, New York. Bill at the time was the #1 ranked 60 year-old runner in the U.S. Ed, then 75, held world records at various distances – an icon in running circles. I was surprised to learn Ed didn’t like to train, in fact he dreaded it. Rather, he trained to race. He simply loved the racing scene. Bill, on the other hand, very much enjoyed both the training and the racing. He found one reinforced the other, calling it a yin-yang relationship. So, here were two top age-class runners, each having their own motivations for running and staying in racing shape. And I expect you have you own reasons too.

Let’s hear from a few other senior runners about why they run:

( Plan to post brief video interviews with six or seven runners soon!)

A few general themes typically emerge, captured, in part, by some humorous cartoons:

It makes me feel good!

I’ve been running with the same folks for over 20 years. These are some of my best friends. We’re all slower, but we’re still doing it!

My doctor loves it when he sees my low heart rate and blood pressure!

Now, let’s briefly look at what the research is telling us about the benefits of participation in endurance sports as one ages.

Physical, social, psychological, mental benefits

A team led by David Geard, PhD, reviewed over 100 studies that explored the benefits of sport on the physiological, social, psychological and mental aspects of masters athletes. While the athletes studied included cyclists and swimmers, among others, I suspect many, if not a majority, were primarily runners as running is the most widely practiced form of exercise. A link to this study can be found on the Research page of TheSeniorRunner.com. Geard’s article, published in 2017, indicated there was strong evidence of positive benefits in all four realms. While many of us believe we enhance our health and longevity through running, as well as feeling better during the non-running hours of our day, we may not think too much about the other three aspects.

But let’s not brush past the physical benefits of running into our 60s and beyond. To illustrate this, while many age-class records have been set in recent years, it’s interesting how this trickles down to everyday runners.

A 2015 study that looked at results of over 600,000 marathon and half marathon finishers showed that 25% of the 65-69 year old runners were faster than 50% of the 20-54 year-olds.

Let’s think about this: one of every four 65-69 year-old runner beat half of the runners who were between 11 to 49 years younger! Of course, many factors come into play here, but that 25% no doubt represents those who have continued to train at a consistent and vigorous level, which I expect is true of many of you following this series.

Muscle mass, capillary and mitochondrial density

On a micro level, studies comparing biopsies of older endurance athletes with those of less active people show significantly greater muscle mass and capillary and mitochondrial density. The combined effect is higher levels of oxygen delivered to the muscles and greater extraction of carbon dioxide from the blood.

We will look at other physical benefits that accrue to seniors from running throughout this series.

Now, let’s consider some social benefits. We can each reflect on the friendships we’ve formed through running. I have lived in various places over the past 47 years. In every place I have quickly engaged with local runners, many of whom became good friends. Running clubs and groups seem to attract a diverse, interesting array of individuals whose common thread is a love of running. Perhaps like me, you consider these running friends “my people.”

Geard’s study compared the number, strength, diversity, and frequency of connections of aging athletes to non-athletes. They called this “social functioning.” They found a strong correlation between vigorous physical activity, which competitive running certainly qualifies as, and the quality and quantity of one’s social networks. In that one’s social connections tend to decrease with age, running can be an important impetus to maintain these connections.

The study looked for evidence of psychological benefits: good mental health, emotional stability, and strong self-concept. The data suggested participation in sport at any age resulted in lower levels of depression, anxiety, better management of stress, and greater overall happiness and self-esteem. And, most important as it relates to senior runners, these positive factors tended to carry over as athletes aged.

For some, success in this realm may be tied to the willingness to adjust expectations. It will vary considerably, but some seniors may enjoy participating in races while being less focused on race time and place.

Mental function was assessed in terms of memory, processing speed, verbal fluency — the stuff we rely on each and every day! Data showed that masters athletes retain more of these mental functions compared to nonathletes. A few studies used fMRI data that showed a greater volume of both white and gray matter. And it follows that increasing blood flow in the brain helps retain neural networks. While anecdotal, we can probably all recall times we got “great ideas” when out for a run!

In summary, there are many good reasons for continuing athletic activities as we age, and for us to run consistently and vigorously!

Take a few minutes to think about why you run, what it means to you, and the benefits you feel it brings.

Now that you’ve reinforced why you run, let’s do a reality check. Those of us who have been running for many years can’t help but notice our cohort keeps shrinking. The numbers bear this out.

About 80% of participants in 5K to marathon races are under age 50. With another 14% in their 50s, that leaves about 6% 60 and older. Many we have run and raced with, some for five, ten, twenty, maybe even thirty or more years are just not showing up. It can be both discouraging and disappointing — we pushed and supported each other and usually shared something about our lives outside of running. Comrades in arms, so to speak! Nevertheless, there are still roughly 150,000 runners worldwide age 60 and older entering races from 5K to marathon.

Why We Stop Running!

The thrust of this series will be looking at strategies to keep us running. Yet, it might be instructive to understand why runners drop out of the sport. While we don’t want to dwell on it, if we keep in mind the minefields others have found, it might enable us to avoid them.

Negative health factors; lack of motivation; fear

Three groups of reasons cited by Peter Reaburn in The Masters Athlete for dropping out of sport are negative health factors, lack of motivation, and fear. Let’s take a look at each of these.

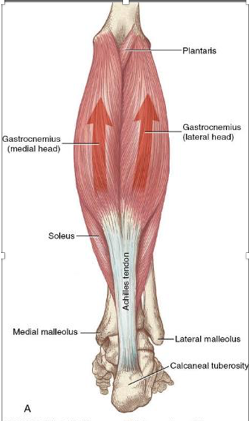

Negative health factors include joint pain and inflammation of key tendons, such as the Achilles tendon and plantar fascia, along with muscle strains and tears.

All of these can become chronic if not addressed. Running with and through pain is neither fun nor healthy and usually leads to more of the same. Pain changes our gait and disrupts the kinetic chain we noted in Chapter 1.

Many of these issues may have developed from poor training habits, perhaps over a number of years. The knee and hip joints are particularly susceptible to wear and tear from bad running form. In later chapters, we will look at strength and flexibility work to support good running form. To the extent we started addressing some of these issues years ago, we have less to fix. But assuming we are able to run, we have a good starting point from which to move.

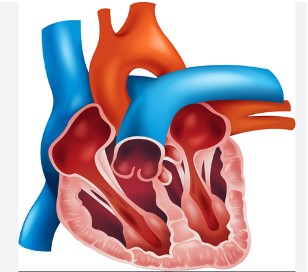

Another negative health factor is cardiovascular complications.

We have a later episode looking at the heart in more depth. Suffice it to say, the heart is an amazing organ. This image shows the basic elements of plumbing that must function in synch when we run (or do anything!) If that doesn’t happen, we are in trouble!

A key thing to remember is the heart is composed of muscle. And as with all muscle, after intense exercise that muscle needs to restore itself. However, unlike our bicep, the heart never stops working (as long as we’re alive!) so rest in this case is relative. But if we constantly push ourselves in exercise and work and do not manage daily stress, we are cruising for a cardiac bruising!

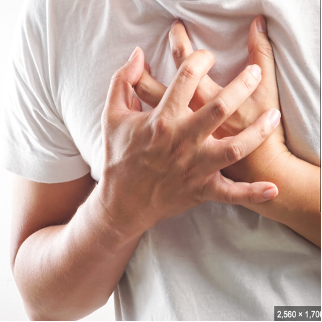

Proxies

Aside from imaging, mostly what our medical professionals have to work with are proxies such as high blood pressure, chest pain, or shortness of breath when exercising.

Obviously, we cannot fool around with this. You must get clearance from your doctor and cardiologist to continuing intense exercise if you have any of these symptoms.

For sure, there are other health-related issues that may make running difficult or impossible, including tragic accidents and chronic illness. But we’ll leave it at that for now.

A second reason for dropping out of the sport is lack of motivation. For many, this is the defining factor. What greater reminder is there we are aging than seeing our race times slow! Not everyone is willing to put in slower, tougher miles.

Eroding race times can be hard to swallow, even when placing well in our age-class or achieving a respectable age-grade % — a topic we’ll discuss in a later chapter. Not seeing the old guard at races and not knowing the young horses coming out of the barn can also make one feel over the hill and a bit out of it. Who likes that feeling!

Something that affects race times and thus motivation is weight gain. Studies show each extra pound costs us about 2 seconds per mile in race time. Thus, a runner 10 pounds over his or her healthy weight (let’s be clear “healthy” does not mean looking like a bean pole!) will lose about 20 seconds a mile – that’s two minutes for a 10K — a lot of time to a competitive runner! Weight can creep up on us. Pay attention to food content labels, hydrate, and eat plenty of fruits and vegetables. We’ll look at food labeling in Chapter 8. If you are carrying a few extra pounds, take the long view on losing it – slow but sure. If you need help with this, find a registered dietitian who specializes in sports nutrition.

Muscle loss

It’s also worth noting that with age, we lose muscle. And it affects our motivation when we find, as have I, that running up hills is harder. I was never a hill-killer, but in younger years I could crest a good-sized hill ready to take advantage of the downside. Now I am flagging halfway up and simply relieved when reaching the top! Part of what’s happening is muscle loss in my legs. About 40% of our total weight is from skeletal muscle. The average person loses about 5% of their muscle each decade after age 50, although athletes tend to lose less unless weight training is their focus. In my case, I weigh about five pounds less than I did 20 years ago but have probably lost 8 to 10 pounds of muscle.

The difference is increased fat, which does nothing to help climb those hills! This added fat does notnecessarily show up as something we can see and pinch. Rather it can be intertwined with muscle and found between and within our organs. So how does this affect motivation?

If we know (and some might suggest it’s better not to know!) what is happening to our body composition, it’s a further hurdle to clear in terms of getting excited about running and racing. But it can also be motivation for engaging in a serious strength training program to build back and maintain muscle.

Fear is another reason why some stop running. We hear about people dropping dead while running. But let’s look at some facts. A 2014 study published in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology showed that while older runners were more likely when running to have a cardiac arrest than a non-exercising couch potato, overall they were only 40% as likely to suffer such an event when compared to the non-exercising population. Flipping this around, this study indicated the non-exercises were 2 1/2 x more likely to have a cardiac arrest than runners. I’ll take those odds! Vigorous exercise, then, is seen as having a protective quality related to the heart. Hardly new news, but still good to keep in mind!

We also hear our joints will give out faster with use. Again, the science does not bear this out. Instead, and while there are certainly individual differences in this, putting pressure on bone and cartilage generally leads to creating more bone and cartilage. This is supported by a 2017 study reported in the Journal of Orthopedic Sports Physical Therapy that found the incidence of hip and knee osteoarthritis in recreational runners was one-third that of nonrunners.

Woolf’s Law

This is evidence of Woolf’s Law, which holds that “bone is laid down in areas of high stress”. Naturally, this assumes one has full function to begin with and is using proper form. Form is an important topic we’ll cover throughout this series.

Feeling Old!

Maybe the biggest fear of all is we will “feel” old in ways we don’t when not exerting ourselves. Let’s be honest – very few – in fact I don’t personally know anyone — who is pumped up about the aging process. We notice it in both big and little ways. A golfing analogy is “playing the ball where it lies.” Some of us may need help navigating the aging process. Don’t delay – get that help if needed.

Celebrating Older Runners!

At races, awards usually start out with younger runners and work their way up. Often the crowd thins by the time the 80-year-olds get their due. More races are reversing this and after announcing the overall winners work their way backwards through the age groups. This is a good trend and should be encouraged. And you may have heard whispers in the crowd when older runners step up to claim their awards: “I hope I’m still running at that age!”

Thank you for reading this chapter. The next one will explore aging: the various ways we define it from a running perspective, the cellular mechanisms by which it occurs, and the ways our various body parts and structures age. And of course, we will offer some things you can do to mitigate the aging process!

Please subscribe so we can alert you when future chapters and blogs are released.