Senior Distance Running Essentials Series

Chapter #3: What is Aging? How We Age (May 2024)

Hello, welcome to the third chapter of Senior Distance Running Essentials.

What does it mean to age? And how does this affect our running? This chapter explores that.

60 to 50; 50 to 40

We’ve heard it said 60 is the new 50, 50 the new 40, and so on. But what does this really mean? It says to me the age on our driver’s license is less important than how we feel, how we engage in the world. And as senior runners, we ask how we feel when running! Certainly, in the later stages of a race, especially on those steep hills, we may find ourselves thinking “it didn’t seem this tough in younger years!”

It can be overwhelming, if not depressing, thinking about the various ways we age and how our rather amazing and intricate bodies change. Yet, we know choices we make affect that rate of change. That is what this series is about! The aim is to give you a sense of assurance that what we do day-to-day in our running, training, and life choices can and will benefit us into our 60s, 70s, 80s and beyond.

In this chapter we will look at some definitions and theories of aging. How is this useful to the senior runner? In chapter #2, we looked at some benefits we might expect by continuing to run as we age. We considered how senior runners are apt to be more active socially and retain more ability to think and confidently interact with what is going on around them. Also, if we do find ourselves injured or ill, we have a better chance to recover or endure.

Overall, we are less concerned about managing activities of daily living (ADLs) than we are about increasing our healthspan, the number of years we live without debilitating chronic conditions.

This is as it should be! The notion of an increased healthspan from vigorous physical activity is supported by the Exercise Is Medicine initiative, developed jointly by the AMA and the American College of Sports Medicine.

Let’s consider two definitions of aging pertinent to senior runners: chronological age and training age.

Aging Defined

Chronological age is important as essentially all road races provide awards by age groups, now increasingly in five-year increments. And chrono age is a key component in age-grading.

The second, training age, warrants some discussion. We might break training age into three components: years, miles, and intensity.

- 1. Number of Years. How long have we been at it? 50 years, five, or something in between? It has been suggested by some coaches and researchers that we might expect improvement in our running for up to 10 years, regardless of our starting point. That may be optimistic if one starts at 60. And, of course, it depends on how fit one is to begin with.

- 2. Volume. What mileage have we been running? Doing the math tells us a runner logging an average of 50 miles a week or 2,500 miles a year for 40 years would have 100,000 miles under his or her belt – about four times around the equator! I haven’t seen an estimate of the number who have run that much, but I suspect it’s more than a few.

“What Does it Take to Run 100,000 Miles?”

A 2017 article in Runner’s World by Amby Burfoot, profiled 20 runners who had run over 100,000 miles.

It included Bill Rodgers, then 69 at 180,000. Three were over 200,000 with the top runner, an 87-year old doctor who had logged 253,000 miles – averaging over 4,000 miles a year, nearly 80 miles a week, for 60+ years. Remarkable or crazy? You take your pick! But compare this to a newer senior runner who has averaged 30 miles a week (more realistic I suggest for a senior runner!) for five years, totaling 7,500 miles. Not shabby – that’s roughly the distance going from New York City traversing the southern U.S to California and back to Manhattan via Canada. But that is just 1/13th as much as a 100,000 mile runner. Now, that is a difference in training age!

- 3. Intensity. And, of course, the quality of those miles is a vital component. More intense training may have allowed for greater racing success over the years. But for some who might have used traditional training methods of ongoing high volume and quality, that could be catching up with them in their senior years.

Evolving training practices

Fortunately, training practices have evolved, with runners of all ages now allowing for more time for recovery, greater emphasis on strength training and mobility, and better nutritional habits. Thus, the likelihood of future senior runners holding their own longer due to these evolving practices is promising.

Can we calculate training age?

Perhaps a mathematical whiz could come up with a formula to calculate one’s training age using the three components of years, volume, and intensity. Maybe that’s already been done. But we’re not going to do that here. Rather we’ll view it in more relative terms.

Theories of Aging

Cells! cells! cells!

Let’s move to theories of aging. We will start in the weeds, at the cellular level.

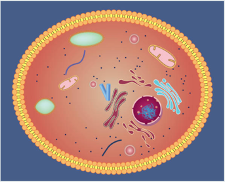

Remember looking at plant cells under the microscope in high school science class? Funny looking things! And those we examined were much larger than most of our cells, an example of which is pictured below Let’s look at some properties of cells that affect our running.

First, we have an immense number of cells, 50-100 trillion of them!. If each cell in our body was represented by a one-meter step, we would have to circle the globe over one million times to account for all our cells. That seems like science fiction, but it’s true. When we run, we are engaging a whole bunch of these cells simultaneously.

Form Follows Function

Second, our cells are organized and specialized to perform specific activities. To do this, cells are of varying size, shape, and properties that follow their function. For example, bone cells vary significantly from muscle cells. Thus, form follows function.

The nucleus is the center of the action!

Third, for all types of cells, the nucleus is the head honcho. This is pictured in dark red. This is where our DNA (what makes us us!) lives and where cell division happens, without which we would literally be one and done.

Fourth, as small as our cells are, there are vital things happening within the cell. A tenet of the science of exercise physiology is cells having membranes, the outer yellow layer on the graphic, that selectively allow solutions to move in or out. And the cell contains organelles called mitochondria, which generate the energy we need to run.

Chemical and thermal equilibrium is vital

For our bodies to function as intended, and for us to run and race as seniors, our cells, whether they are found in the heart, brain, muscle, bone, or skin must function within a narrow a range of conditions. Our bodily systems work together to maintain chemical and thermal equilibrium. If such balance is thrown off, either it is restored quickly or we’re history!

So, those are some basics of about cells and their structure and function. It is background we’ll draw on in the series.

Now, let’s look at some theories of aging.

Cellular degeneration

Cellular aging theories generally revolve around degenerative changes within cells which result in too much of some things and too little of others.

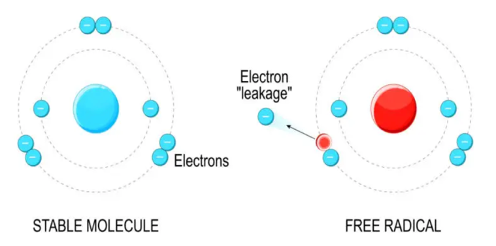

Free-radical oxidation is thought to be a primary cause of this degeneration. As shown here, free-radicals have an unpaired electron that spins out of the normal orbit, creating unstable molecules that interfere with normal cell activity. It’s not that this is unexpected. Rather,

free-radicals are a normal part of metabolism. And when we exercise vigorously, this increases our rate of metabolism, which tends to generate more free-radicals. Certain parts of cells are affected more than others by free-radicals. For example, mitochondria, our energy powerhouses, which also help regulate metabolism and promote cell growth, are particularly susceptible to the presence of free-radicals. Thus, taking them out of action has various negative implications for the cell.

Oxidases to the rescue!

The good news is the body responds to this activity by producing oxidases, which are enzymes that work to clear free-radicals. The bad news is with aging our ability to produce oxidases declines. So, what to do? A healthy diet with plenty of fruits and vegetables and less ultra-processed foods, quality sleep, managing stress, and regular exercise are all known to help maintain oxidase levels.

The wear-and-tear theory purports that accumulated toxins and viruses lead to accelerated cell death while limiting protein formation. This, then, potentially affects all cells, tissues, and organs in the body. An obvious approach is to limit our exposure to these things.

With aging we generally feel stiffer. This affects the fluidity of our stride as well as stride length and thus race times. The cross-linkage theory suggests that collagen molecules join together to form larger molecules that resist repair processes and lead to a loss of elasticity in tissues throughout the body. Staying active is the key thing we can do here! That doesn’t mean we need to join the 100,000 mile club! But stretching and yoga can help to realign collagen fibers that have joined.

Genetic theories

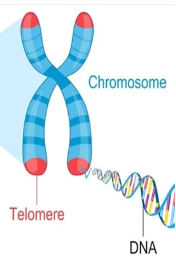

Within our cells’ nucleus reside 23 pairs of chromosomes, which contain a combination of many thousands of genes. These genes determine how we interact with the world, including such things as our proportion of slow-twitch vs. fast-twitch muscle fibers.

It is generally agreed that while one’s genes are of primary importance, expression of those genes is directly affected by the environment we grow up in. This includes our choice to run and the response to training stimuli.

One genetic theory of aging revolves around the shortening of telomeres.

It has been observed that telomeres, or the ends of the chromosomes that make up our DNA, tend to shorten with repeated divisions. If unchecked, this restricts the cell’s ability to divide, leading to cell death. It seems every couple of months a new drug or magic elixir is espoused to address this. This may come, but for now, we should rely on a diet rich in legumes, nuts, fruit and dairy to help rebuild and lengthen our telomeres.

Total and cumulative effect of cellular theories

We’ve just looked at a variety of cellular changes affected by aging. Are these happening in some of us and not others? While we might want to think we are exempt from such processes, the likelihood is we are all subject to these changes but at different rates due to both internal and external factors. I find it a bit scary to think all of this is happening in our bodies. Our best choice is to focus on doing what we can to support good health and bodily function, such as good nutrition, restful sleep, and avoiding toxins.

Control Theories

As noted in Chapter 1, our bodies are designed to self-regulate. This is done by our control systems, notably our immune and endocrine systems. As we age, the effectiveness and resilience of both systems decline, thus reducing our ability to ward off systemic inflammation and foreign body invaders. This was a key reason why seniors received priority for vaccination against the coronavirus. Also, reduced output of growth hormones and testosterone with aging affects regeneration of muscles, ligaments, tendon, bone, and cartilage. However, strength training stimulates this output and we’ll look at this later in the series.

The Macro View

Now, let’s zoom out while keeping in mind the whole is the sum of the parts. For example, our legs are composed of millions of cells all potentially subject to the impacts of aging discussed above.

As noted in Chapter 1, we have 206 bones and about 500 joints. We may learn the names of these when we break them or consider replacements! The hard (or not so hard!) truth is that bone density decreases with age, leading to osteoporosis and an increased chance of fracture. Some accept this as just what happens when we age.

But one of the best protections is weight-bearing exercise. Running certainly qualifies!

Recall Woolf’s Law — “bone grows in response to demands placed on it.” To some degree, this also applies to cartilage. Again, no need to join the 100,000 mile club. But we are privy to perhaps the most accessible weight-bearing exercise there is!

Let’s now consider how aging affects our neuromuscular system; the 640 muscles, 900 ligaments, 4,000 tendons, and 45 miles of nerves.

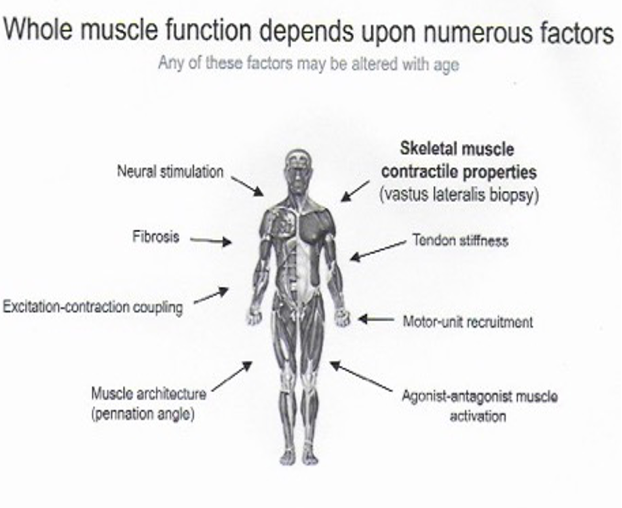

Consider the below graphic created by Mark Miller at UMass Amherst showing factors that are typically altered with age.

Dr. Miller’s point is that whole muscle movement, which we employ when running, is influenced by all of these factors acting simultaneously and cumulatively. We may revisit this diagram later in the series.

For now, let’s look at one of those factors: fibrosis. This describes a thickening or scarring of tissue, such as occurs in our hamstring from a grade 2 or 3 strain of the tendons that connect the hamstring to our bones. The result are hamstrings and tendons that lose some of their flexibility. This may reduce that leg’s stride length, impacting gait, and lead to problems connected to poor form. And stiff tendons are more apt to strain or tear. Once that happens repair can take a long time, as they have limited blood flow.

The answer, naturally, is to be proactive in addressing these imbalances with daily physical activity and modalities such as PT, massage, and yoga to clear the scar tissue.

We’ve covered a lot in this episode. And I suspect some (maybe most!) of this is unwelcomed news. But if you are following this series, I expect you are the type who wants to understand the intricate workings of our bodies and what we can do in our training and daily lives that give us the best chance of experiencing healthy aging and allow us to keep running.

Thank you for reading this chapter. Please forward the link to friends you feel would enjoy the series and if you not already done so subscribe so we may alert you when updates are posted.

Meanwhile, stay healthy and keep running!